Robert Weaver Stop Me Before I Kill Again

She woke up. She felt his weight pinning her to the back seat of the car. She felt his arm tight against her throat, squeezing. Felt her wrists in handcuffs behind her dorsum. Duct tape stretched around her caput, roofing her olfactory organ and mouth.

Tiffany Taylor was being raped.

He spoke. Don't worry, he said. He had washed this before. When he finished, he would carry her trunk to the torso of the car.

She cried. She bit her tongue, and it bled. Her tears and claret loosened the record. She screamed. Don't kill me. Delight. Don't kill me. I'm pregnant.

I know, he said.

'I wasn't planning on dying that twenty-four hour period'

Scroll downwardly for the full video of Tiffany's story about how she managed to escape with her life.

In the summertime and fall of 2016, a serial killer stalked the streets of urban New Jersey.

He attacked four women in 84 days. He killed three.

He used his telephone for everything. To chase women. To learn faster ways to kill. When a murder was consummate, he asked his phone for directions home.

After most trigger-happy crimes, victims and their loved ones must wait, hoping police and prosecutors may someday bring the criminal to justice.

For the women affected by these crimes, hope wasn't good enough.

And for Tiffany Taylor, waiting wasn't an choice.

Law didn't crack this instance. Women did.

Women outsmarted the killer. They constitute him. And they stopped him.

Robin Westward met her two best friends in a jail bearded as a schoolhouse.

As a teenager, she lived for a fourth dimension at Wordsworth Academy, a treatment facility in West Philadelphia for immature people with behavioral and mental wellness problems. Information technology was a identify with holes in the walls and exposed electrical wires — a place where news reports detailed how counselors regularly raped and shell their charges.

In that dangerous place, West met Tracey Johnson. Typically silent, Due west opened up to Johnson, who was two years older. She talked almost going to Sanctuary Church building of the Open up Door in Philadelphia with her mother. West was such a good singer, occasionally she led the choir.

"From in that location, nosotros but grew a crazy close friendship," said Johnson, 25. "She was family."

Wordsworth is too where West met Breneisha Patterson, when both girls were just fourteen. They grew so close they called each other "sis" and "twin."

"We acted alike. We were e'er together," Patterson said. "Blood couldn't make the states no closer."

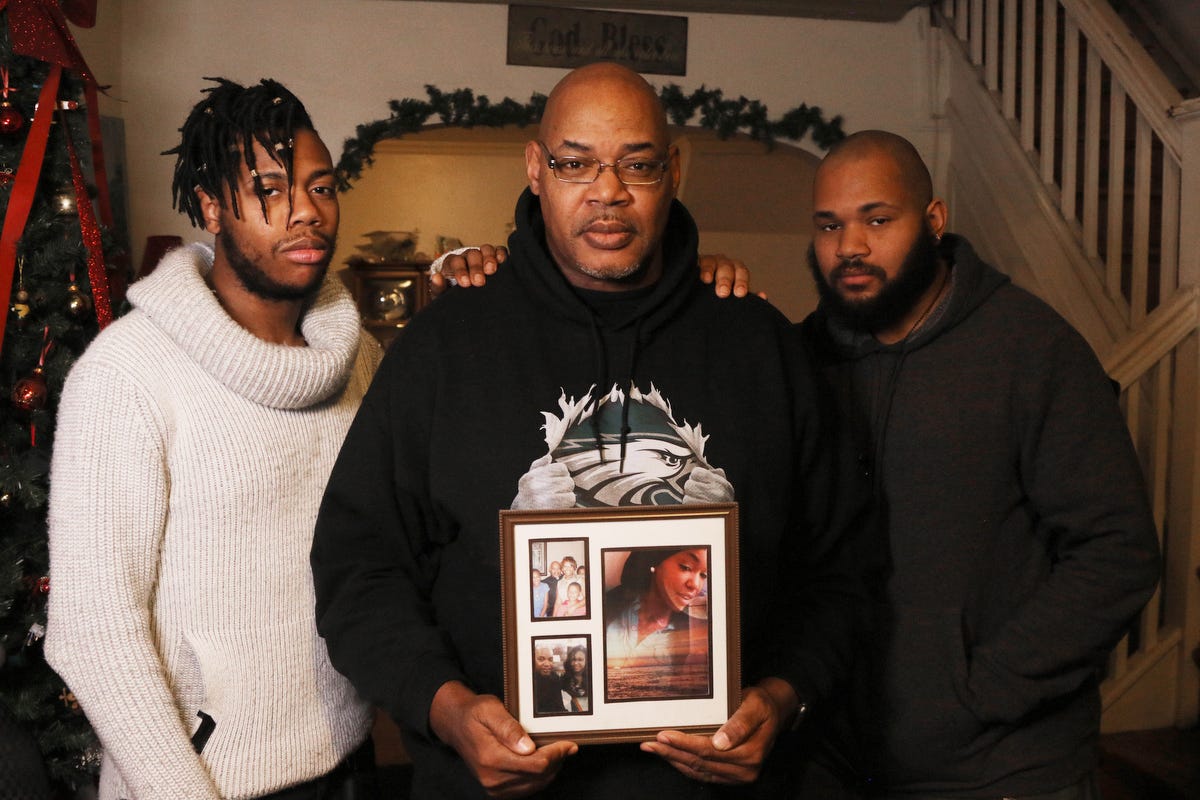

West lived most of her babyhood with her mother, Anita Mason, in West Philadelphia. Occasionally she stayed with her father, Leroy West, a Philadelphia school district law officer and assistant church pastor who lives on the city's north side.

When Leroy West imposed rules similar an evening curfew, his daughter chafed.

Robin was very adventurous. Very potent-willed. It really didn't matter what anybody felt. If she made up her ain mind to do something, she would do information technology.

"Robin was very adventurous. Very strong-willed," said Due west, 56. "Information technology really didn't matter what anybody felt. If she made up her own listen to do something, she would practice it."

West and her female parent fought often, co-ordinate to an interview Mason granted in 2017 to the Philadelphia radio station WHYY. Mason declined to be interviewed for this story. West moved out of her mother's house when she was 18.

The people who loved Due west learned to utilise Facebook to rails her moods. When West felt happy, she posted Facebook photos with her hair dyed blond or mint green. When she felt low, she dyed it black. West was looking frontwards to Sept. 5, 2016. Information technology was to exist her 20th birthday. She posted photos on Facebook of a sleeveless white dress, which she bought for the occasion.

West'southward style helped her win clients at Cheeks 247 Lounge, a now-closed club in W Philadelphia — one of several where she worked as an exotic dancer.

"She cried about how her parents could never accept her," said Quadavia Williams, who trained West to strip. "Robin liked going out, hanging out with her girlfriends. Her parents were churchgoing people."

West and Patterson were as well sex workers, often pairing upwardly to continue each other safety. They placed ads on websites, coming together johns at hotels in Philadelphia.

At the end of August 2016, Patterson suggested a trip to New Bailiwick of jersey.

The two stayed at the Garden Land Motor Lodge in Matrimony Township, 15 miles from Manhattan.

After a few nights they found themselves out of greenbacks, with no identify to stay.

So at eleven p.chiliad. on Aug. 31, the pair headed to Nye Avenue in Newark, a neighborhood of burned-out homes and weedy lots framed by an abandoned train yard.

Due west wore a red Nike hat, a lacy black shirt and black shorts. Her blackness sandals sparkled in the orangish glow of streetlights. It was her first dark walking the street.

W didn't really know the ropes, Patterson recalled.

One of the beginning cars to cease was a silver sedan. The commuter seemed overnice. Charming.

"Who you lot desire?" Patterson asked.

The commuter pointed to West. She got into the automobile.

Patterson typed the car's license plate number into her phone. She saved it as a contact.

As the motorcar pulled abroad, Patterson told the commuter, "Be careful with my sister, considering I beloved her."

Data from the driver's telephone captured what happened next. He drove to an abandoned house at 472 Lakeside Ave. in the city of Orangish, two miles from his home. He spent an hour within. He left at 1:27 a.m.

Twenty-iii minutes later, a neighbour called for assistance. The abased house was on fire.

The killer drove west. He traveled a few miles on Interstate 280. Then he backtracked. He passed his own home in Orange before returning to the fire. Five cities sent firefighters. The killer watched them attack the called-for house.

Inside, firefighters found a body.

"It was the most destructed trunk I've e'er come up across," said Matthew Piserchio, a 17-year veteran with the Orange Burn Department and the metropolis's lead arson investigator.

The business firm continued to burn down. The killer asked his phone for directions home.

The post-obit day, Patterson reported West missing. She gave the license plate number to Wedlock Township law. The plate belonged to a silver BMW.

The body discovered within the burned house was and then badly damaged, investigators used dental records to identify W. The determination came two weeks after she went missing, on Sept. 13, 2016 — eight days after West'south altogether.

Joann Brown was born in Augusta, Maine. She had a sister and six brothers. They called her "Billy Jo." When she was 5, the family moved to Newark. Her childhood was difficult. Dark-brown adult bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, but she retained a lightness. Brown graduated from West Side High School. She enjoyed fashion and styling hair.

Fifty-fifty when her mood suddenly turned nighttime she would recover, laughing and dancing with her friends.

Her joy pulled people close. So did her abundant pain.

"She's my best friend," Amina Nobles said of Brown. "She had bug when she was young. That's what made me depict to her because she used to come up to me and talk to me about her bug."

I always used to ask her, 'Will you lot want to e'er alter?' Just she said that that's the just way how she gets her money.

Brown used drugs. She worked as an exotic dancer for about a decade, starting time under the street name "Secret" and later as "London."

She was also a sexual practice worker. Friends worried for her condom.

"I e'er used to ask her, 'Will yous want to always change?' " Nobles said of Brown's sex work. "But she said that that's the but fashion how she gets her money."

Chocolate-brown looked for help. She moved into a building run past Projection Live, a nonprofit group in Newark that offers housing, drug treatment and counseling. In an environment that relied on rules and a regular schedule to counter the anarchy of the streets, Brown struggled.

"She was prostituting, and had a lot of male friends supporting her," said Christine Edwards, Brown's social worker at the program. "It was difficult with her to become her to proceed a lot of her [counseling] appointments."

Brown and Nobles were hanging out with friends nigh a Popeyes restaurant on Newark'southward s side on October. 22, 2016. Brown was 33.

He arrived at ane:xvi p.m. He chose Brown.

Commonly when she left with a client, Brown called Nobles to report her whereabouts and the fourth dimension she expected to return. In her dangerous profession, the telephone call provided a tenuous lifeline. On this afternoon, however, another friend in the group needed to make an urgent phone call.

And then Dark-brown handed her phone to her friend. Then she got into the car.

As they drove, Brown asked to borrow the man'due south phone. She called Nobles at 1:thirty p.chiliad. Cellphone towers recorded the phone's location to inside a few meters.

The destination was an abandoned house at 354 Highland Ave. in Orangish.

He knew the identify well. Immediately earlier driving to Popeyes, he had spent 21 minutes inside, preparing for this moment.

He took Dark-brown inside. He wrapped her head in duct tape, from her optics downward to her chin. He strangled her with a jacket. He left her body on the landing of the stairs.

At iii:03 p.m., the killer left.

Two minutes later, he arrived abode. Iv minutes after that, he searched his phone for recent outgoing calls. He called the number at the top of the listing.

Nobles answered.

She asked: "Is this London?"

The killer stayed silent.

"The person didn't say anything," Nobles said.

Nobles called the number back three or iv times. No one answered. Nobles reported her friend missing to Newark police force.

"She always called me. Every twenty-four hours," Nobles said. "This time something wasn't right."

Seven weeks later, on Dec. 5, a pair of contractors arrived at 354 Highland Ave. The home'south possessor had requested an gauge to gear up it upward. The workers scouted the get-go floor, and then walked upstairs. At the landing, the first man stopped.

"Boss," he said. "I think somebody'south sleeping in hither."

Anybody knew he was the tranquillity one.

Orange is a small urban center, located only west of Newark and encompassing 2.2 square miles. Most kids who grow up here know each other by confront, if not by proper noun, by the fourth dimension they attain middle school.

Khalil Wheeler-Weaver had few friends. He didn't play sports, rarely attended parties and didn't date, according to neighbors and classmates from the Orange Loftier School class of 2014.

"I know he didn't have girlfriends at all in high school," said Tyrell Benton, a classmate now studying informatics at Rutgers University in Newark. "He kept to himself. He wasn't popular, merely he wasn't bullied, either."

His friends saw a different side.

"Khalil is the funniest guy you could always meet," said Richard Isaacs, Wheeler-Weaver's best friend. "He doesn't talk too much. Simply when he does talk, he'south hilarious."

Wheeler-Weaver likewise stuck out for his nerdy style. He wore plaid shirts tucked into ironed khakis and plain white Nikes.

"You lot have to wear Jordans, the newest ones that just came out. ... Your shirt has to match your sneakers and your hat. That'south what y'all wore if yous were going subsequently the females. Information technology was a street style," Benton said. "He wasn't a street kid. Yous knew based on how he dressed that he came from a practiced home, a good family."

Orangish is a post-industrial city where one person in four lives below the poverty line. Merely Wheeler-Weaver grew up in a comfy split up-level business firm, in a serenity neighborhood called Seven Oaks. His stepfather is a police detective in the neighboring town of East Orange, and his uncle retired as a detective after a career with the Newark Law Department.

By his late teens, Wheeler-Weaver seemed to mature. He was alpine and proficient-looking, with broad-set chocolate-brown eyes and a charming grinning. He started to DJ parties. He bought a silver BMW. When Isaacs dated a freshman at Rutgers, Wheeler-Weaver started dating her roommate.

He became a security guard. He used his phone to explore becoming a police force officer, researching the required exams and grooming.

He also used his phone to research "bootleg poisons to kill humans."

Tiffany Taylor came to fear Khalil Wheeler-Weaver. Came to hate him. But she never ceded him power. So long as she remained conscious, she believes, she remained in control.

"I think I always had the upper hand, actually," Taylor said on a chilly 24-hour interval in December, sitting on a puffy bluish burrow in her new apartment in Jersey Urban center. "Because he's actually young. He'south not experienced with people. And he'due south just so stupid."

Taylor grew upwardly in the Salem Lafayette apartments, a public housing project in Jersey Metropolis. She moved with her mother to Orlando, Florida, where she attended Valencia Higher. She studied psychology and music, and she danced professionally in stage shows. After two years in Florida, she got pregnant, left college, and moved back to New Jersey, where she worked equally a sex worker.

Taylor met Wheeler-Weaver through a friend. She was 33 and living in Roselle with her mother. Wheeler-Weaver was twenty, too young fifty-fifty to purchase beer. When they hung out, Taylor drove her Volkswagen convertible to Wheeler-Weaver'due south house in Orange.

Taylor kicked his butt at NBA 2K, a basketball video game. She called him "Young'un."

He liked her tattoos. Her dreadlocks. The fact she could bulldoze a stick-shift car.

"He was obsessed. He kept asking my friend to hook u.s. up," Taylor said. "I kept saying no. Because he was young. And he was sleeping with my friend. I just didn't want to deal with him."

Wheeler-Weaver kept begging to pay her for sex activity. Somewhen she said yes, although that was a lie. Instead, she planned to rob him.

"I just got tired of men just wanting sex from me all the fourth dimension, looking at me like I was a sex object," Taylor said. "So I just started taking their money."

Wheeler-Weaver texted Taylor his address, summoning her to the white split-level in Orangish. She arrived at around viii p.yard. on April 10, 2016. He paid $200 cash, upward forepart, as agreed. They walked upstairs. She entered his childhood bedroom. She saw a nightstand and the tiny bed of a boy.

Wait, she said. I forgot the condoms in my machine. Let me become get them. Taylor walked outside. Cash in mitt, she collection away.

After that, Taylor'due south life unraveled.

Her female parent was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. They couldn't pay the medical bills, or the rent. They were evicted from their Roselle apartment. As winter approached, they slept in a auto.

By November 2016, Taylor had a new hustle. A construction worker and drug addict she knew rented Room 32 at the Ritz Cabin, a tidy but dreary place on Route 1 in Elizabeth. The addict endemic a burgundy Lincoln sedan. He gave Taylor the keys. He instructed her to employ the car to find dealers and buy him scissure. In return, he paid her cash.

Meanwhile, Taylor kept receiving texts from a stranger. In her line of work, this was non uncommon. The human begged for sex activity. When Taylor inverse phones, he found her new number and kept texting. When she declined, he offered more than money.

Taylor finally agreed. The date was Nov. xv, 2016.

Her plan: Steal his coin, then get away.

The stranger arrived at the Ritz at 7:51 p.m. Information technology was l degrees, but he came dressed for snow. He wore blackness gloves. His brownisheyes were framed by a black ski mask, a hat and the hood of his black sweatshirt. His wearing apparel curtained handcuffs and a roll of duct tape.

Taylor didn't recognize him. She knows people who clothing ski masks in the cold, she said, so she didn't find his outfit odd. Her focus was the money. He paid her $80 greenbacks.

Taylor collection the Lincoln from the Ritz. The man in the ski mask rode in the passenger's seat. He asked Taylor to pull over so he could urinate. It was a ruse.

It seems likely that he bashed her on the head, perchance with the handcuffs. Or perchance he slipped a date rape drug into her iced tea. Either mode, Taylor lost consciousness. When she woke up, her caput thundered in pain. She couldn't breathe. He pressed her body into the back seat, her neck in a choke agree.

"I thought I was going to die," she said.

Equally she regained consciousness, the stranger removed his ski mask.

Wheeler-Weaver looked at Taylor and paused to innovate himself.

"Do I look familiar? You don't remember me?" Taylor remembers him saying. "You took my money."

She screamed. Don't kill me. Delight. Don't kill me. I'm significant.

"I know," Wheeler-Weaver said.

This is when she knew. He would kill her tonight.

Under the loosened duct tape, she cried. Please. The handcuffs are and so tight. Could you loosen them?

He did.

"Once he agreed to that, in my caput I said, 'I got him,' " Taylor said. " 'He'south weak.' "

She kept talking. Y'all texted me, remember? My phone has our unabridged conversation. It has your Facebook business relationship. Your accost. Your name.

Simply my phone isn't here. It's back in Room 32. Back at the Ritz.

"Oh, no," Wheeler-Weaver said, his tenor voice rising. "We got to get back and get that phone."

He loosened his grip on Taylor'southward neck. He moved to the front end seat. For a moment, he cast himself as the victim.

"Nobody wants me. Nobody likes me. Why exercise I take to pay for a girl to show me attention?"

He started the car.

Documentary: NJ Serial Killer Khalil Wheeler-Weaver

Surviving serial killer Khalil Wheeler-Weaver: Tiffany Taylor

To catfish a killer: How a serial murderer was outsmarted and stopped

NJ series killer Khalil Wheeler-Weaver: Behind the scenes of the reporting

Series killer Khalil Wheeler-Weaver found guilty on all counts

Taylor is double-jointed. Alone in the back seat, her wrists behind her back, she folded her left thumb into her palm. She pulled her hand complimentary of the cuffs. He didn't notice.

She made her determination.

If this guy drives past the Ritz Motel without stopping, she would drop the handcuffs over his head. When the chain reached his neck, she would pull with all her strength. Perhaps Taylor would die in the crash. She felt prepared to accept information technology, so long as Wheeler-Weaver died, too.

When he pulled into the Ritz parking lot, Taylor was surprised. She abandoned her plan to kill him. Rapidly, she slipped her left hand back into the cuffs.

Wheeler-Weaver parked, opened the back door, and tore the duct record from her face. He draped a jacket beyond her shoulders to hibernate the cuffs. He explained the plan. She was to walk upstairs. He would trail a few feet backside. She would retrieve the telephone. They would leave together.

Taylor said yes. She climbed the stairs. She arrived at the mustard yellow door of Room 32. She kicked the door. The addict, desperate for his drugs, opened it immediately.

Just as Taylor planned.

She rushed in, and slammed the door close. The deadbolt locked automatically.

Wheeler-Weaver ran to the door. He shouted. You lied. Come up outside. Taylor opened the green drape on the window next to the bolted door. She raised her right wrist so he could see. The handcuffs dangled. Wheeler-Weaver ran away.

Seconds afterward, Taylor tried to lay a trap. She texted Wheeler-Weaver. You have the keys to the Lincoln, she said, but the car'south non mine. Bring back the keys, and I won't call the law.

"Well, I had already called the constabulary," Taylor said. "I tried to set him upward. I was hoping he'd come dorsum with the car keys and the police force would come at the same fourth dimension."

Wheeler-Weaver did render. The motel's security cameras recorded information technology. He ran back onto the belongings, dropped the keys on the motel stairs, and so ran away.

"He came back!" Taylor said. "He knew I'g a sneaky bastard. I had already lied to him like three times! How stupid tin he be?"

Officers from the Elizabeth Police force Section arrived at the Ritz at ix:28 p.m. Wheeler-Weaver was yet there, watching police from the shadows. He asked his phone for directions dwelling and at nine:38 p.m., collection away.

Taylor described the kidnapping, rape and attempted murder to the cops. She knew the assaulter's phone number. His Facebook account. His home address. She even told the cops his full name: Khalil Wheeler-Weaver.

The police force didn't mind. They accused Taylor of prostitution. They threatened her with arrest. Taylor was four months pregnant. The killer's handcuffs dangled from her wrist. The cuffs made her feel similar Wheeler-Weaver was still at that place, strangling her. Taylor begged the cops to remove the cuffs.

For an hour, they refused.

"They treated me similar trash," she said.

Elizabeth Police force Director Earl J. Graves did non respond to calls and emails seeking comment for this story. At Wheeler-Weaver's trial, Constabulary Officer Baton Ly was asked whether he had believed Taylor'due south story.

"Um, not really," Ly said.

Speaking to the jury, Banana County Prosecutor Adam Wells did non hide his contempt.

"The police treat her as a suspect. They do not take her seriously. They are dismissive. They human action, bluntly, disgracefully towards her," Wells said. "Talk almost a nightmare."

Seven days after Taylor escaped, Wheeler-Weaver killed once more.

Sarah Butler was 5 when she discovered dance. She was walking with her big sister, Bassania Daley, and their mother in Montclair, a suburb 15 miles west of Manhattan. They stopped at the window of Premiere Trip the light fantastic Theatre to lookout a course.

They walked inside and signed up. Daley attended but a few classes. Butler fell in dear.

She studied a fusion of ballet, modern, jazz and African dance. Butler joined the Montclair Loftier School dance company. At age fifteen she joined Premiere's traveling troupe. In June 2016, they competed in the Apollo Theater'due south famous amateur night. Butler led her team to a third-place finish.

"Sarah didn't have the typical dancer'southward torso," said Shirlise McKinley-Wiggins, founder and director of Premiere. "Our stuff is not e'er easy. It tin be fast. Information technology tin be very able-bodied. She had to work for everything."

The same applied to the entire Butler family. Sarah's mother, Lavern Butler, emigrated from Jamaica in the early 1990s, eventually becoming a nanny in Montclair. She married Victor Butler, a bartender at a state club. They raised three daughters. Money was tight. Sarah Butler worked multiple jobs, eventually saving plenty for a used machine. Later on graduation, she drove 15 miles to New Jersey City University — the starting time member of her family unit to enroll in college.

Simply she struggled to make friends, and didn't get forth with her roommates.

"She didn't like it there," Butler's friend LaMia Brown said in court. "But she was in schoolhouse, so she had no option."

Butler created an account on Tagged, a social media site users draw every bit a place to find companionship. In that location she saw the profile of a man who called himself LilYachtRock.

He typed: "u wanna make $$?"

And then: "sex activity for $?"

"wow," Sarah Butler texted dorsum. "well, how much money?

"how much are yous looking for?" he wrote.

"$500," she texted.

V hundred dollars was a lot of money. Notwithstanding, she wavered.

"Youre not a series killer, right? lmao," Butler texted LilYachtRock.

"No," he replied.

He wanted to run into soon, he said. He needed to leave for work.

Butler agreed to come across. At the last minute, she changed her heed. She stood him up. 2 days afterward, she reconsidered.

"Sorry most the other solar day. I got really nervous," Butler wrote back. "I felt like an donkey. But your vox and ya motion-picture show don't seem like a match."

LilYachtRock responded: "im a actually absurd guy when you get to know me".

On Nov. 22, 2016, the first solar day of Thanksgiving pause, Lavern Butler collection her blue Dodge minivan to Jersey Urban center to call up her daughter from school. That evening, Sarah asked to borrow the minivan. She wore a ruby pilus extension in a ponytail.

She collection alone into the clear windy nighttime. She picked up LilYachtRock at the address he provided: the abandoned house at 354 Highland Ave. in Orange.

Within, Joann Chocolate-brown's body lay on the second-flooring landing, where he had left her exactly one month before. Her face was notwithstanding wrapped in duct tape. Outside, Butler pulled upwards in her mother's blueish minivan. Wheeler-Weaver climbed in. Information technology was 9:55 p.m.

They drove to a 7-Eleven store a few blocks away. She stayed in the minivan. He got out. He purchased three Trojan Burn down & Water ice condoms.

Security cameras captured his outfit, the same 1 he wore to attack Tiffany Taylor: a black sweatshirt with the hood pulled low over his face, black sweatpants, black sneakers and tight-fitting black gloves.

At x:07 p.1000., they drove away. The minivan climbed the wooded hillside of Hawkeye Rock Reservation, an Essex Canton park in West Orange. In that location on a cliff stands Highlawn Pavilion, a restaurant and wedding venue with a panoramic view of Manhattan.

Four hundred feet from the forepart door, the restaurant's valet lot sits backside a scrim of copse. A green trailer leans on jutting tires at the border of the lot.

The night was cool and clear. The view of the Empire State Building was excellent.

This is where Wheeler-Weaver murdered Sarah Butler.

He dragged her trunk behind the trailer. He was sloppy. He allowed her heels to carve parallel trenches in the soft ground. He left sweatpants tied tightly around her throat. When he removed the packing tape from her caput, information technology ripped out scarlet fibers from Butler's hair extension. He deposited the tape within the van.

He covered her trunk with leaves and twigs. Her hands and feet were left exposed to the stars.

Danielle Parhizkaran and Tariq Zehawi/NorthJersey.com

Butler was supposed to render home with the van at 8 p.m. When she didn't arrive, Bassania Daley started texting friends, asking if anyone had seen her sister. In the morn, Lavern Butler phoned her daughter. Her calls went to voicemail. A panic rose.

On Nov. 25, 3 days after Butler went missing, Bassania Daley's friend spotted the blueish minivan. Information technology was tucked behind a one-time factory, 4 miles from Butler'south street, half-dozen blocks from Wheeler-Weaver'south house.

Law arrived at the scene, as did Daley and a friend, LaMia Brown.

The cops hadn't notwithstanding noticed Butler's red weave. Butler's sister did. LaMia Dark-brown let out a scream. She pointed to the hair extension on the ground. Beside it saturday the aforementioned blueish plastic trash can Butler's mother liked to keep beside the driver's seat.

This was all the proof they needed. Sarah Butler wasn't simply missing. She was in danger.

The women decided to take matters into their own hands. They drove to Butler's home and opened her laptop. Brown knew the password, then they searched Butler's email and Facebook. Daley'south friend Samantha Rivera joined them.

"The purpose was to try to find clues," Daley said in court.

They logged into Butler's account on Tagged. They saw she had been chatting with a human called LilYachtRock.

Daley read the exchange.

"You wanna brand $$?"

The women decided they had to notice LilYachtRock.

Samantha Rivera created a profile on Tagged, using someone else'southward photo and a fake proper noun. LilYachtRock'southward profile was among the first to appear. Rivera clicked a button on his profile, sending him a "thumbs upward."

In the days afterwards Butler went missing, Daley and her friends spent lots of fourth dimension at Montclair police headquarters, giving statements and waiting for news. They were standing within the station on Nov. 26 when Rivera received a text on Tagged.

It was LilYachtRock. He began by offering cash for sex activity. He said his name was Tahj. He needed to meet presently, earlier he left for work.

The coin, the blitz, all of information technology mirrored his texts to Butler before she disappeared. Immediately, the women were suspicious. Equally letters progressed to a call, Rivera pressed a button to place LilYachtRock on speakerphone. Daley, thinking on the fly, opened the photographic camera on her own phone and recorded the conversation on video.

The women all the same were standing inside police headquarters.

LilYachtRock didn't catch on. He wanted to encounter Rivera, before long.

"Practise you want me to cease on past?" he said.

The women had to think fast. They needed more information, more than time. Rivera lied. She was doing her pilus, she said. She had a baby at domicile, so she couldn't leave until her sister arrived. She initiated a three-mode phone call with Daley, who pretended to be her sister.

Every bit she stalled, Rivera baited the hook. She wanted to run across for sexual practice, she said. And she was desperate for money.

"I live with my sister right now, and don't want to be here," she told him. "I want to exist somewhere else."

Somewhen, Rivera said she would meet LilYachtRock at a Panera Staff of life in Montclair, a mile from police headquarters. After hanging upward, they went to the cops inside the station and described the planned meeting. The three women stayed there; police sent two detectives instead.

Confronted at Panera, LilYachtRock gave the officers his real name: Khalil Wheeler-Weaver. The constabulary would afterwards say they had no trunk, no evidence of a law-breaking, no reason to consider him a suspect. They let him go.

Meanwhile, authorities likewise followed the trail of Butler's iPhone, which sent its last location ping from Eagle Rock Reservation the night she disappeared. On Dec. 1, police establish her torso, lying in weeds by the valet parking lot.

Thank you to the efforts of Bassania Daley and her friends, constabulary were already homing in on her killer. Five days after Butler'southward torso was discovered, on Dec. six, 2016, Wheeler-Weaver was in custody. All communications by LilYachtRock and his other false names — Tahj and pimpkillerghost — stopped permanently.

These women "are the first true heroes in this case," said Adam Wells, the atomic number 82 Essex County prosecutor in Wheeler-Weaver's murder trial.

Khalil Wheeler-Weaver made many mistakes. And yet he proved difficult to grab.

When he searched ways to kill people with bleach, he used his phone. When he met Robin W, drove her to an abandoned business firm, murdered her, burned the house to the ground, and returned to spotter the burn, his phone sat beside him, recording his location.

When Joann Brown borrowed Wheeler-Weaver's telephone to phone call a friend, that telephone pinged a forest of prison cell towers, creating a digital trail that led prosecutors to the empty business firm where he killed her.

When he attacked Tiffany Taylor near the Ritz Motel, and when he murdered Sarah Butler in Hawkeye Rock Reservation, his telephone was at that place. And it was on.

Law from two cities — Montclair, dwelling to Sarah Butler; and Union Township, where West had stayed in a cabin — interviewed Wheeler-Weaver during his spree. Both times, Wheeler-Weaver accompanied officers on driving tours. He showed police where he met Butler and West, where they drove together, and where he last saw each woman — prophylactic and live, he said.

Everything he told the police was a lie. His phone records later proved it. Until they discovered Butler'south torso on December. 1, constabulary found no evidence that a crime had even occurred.

"At the time in that location was no manner of knowing he was a doubtable, or if she was missing," Capt. Scott Breslow, who supervises the Union Township law detective bureau, said of Wheeler-Weaver and Robin West. "Basically for united states, information technology'south a missing person. It's a basic thing."

To catfish a killer: How a serial murderer was outsmarted and stopped

Khalil Wheeler-Weaver killed iii immature women in Essex County, NJ in 2016. He was eventually defenseless, thank you to the friends and family of 1 of them.

Chris Pedota and Christopher Maag, NorthJersey.com

Nor was it piece of cake to prove his guilt. Prosecutors took three years to investigate Wheeler-Weaver's crimes earlier bringing their case. Their prove ranged from traditional canine searches to cutting-border tools like the Zephyr machine, a device created by NASA that immune investigators to cook Wheeler-Weaver'southward smartphone and harvest its data without his password.

But police force didn't crevice this case.

Women did.

Women who never investigated a murder in their lives.

Breneisha Patterson recorded Wheeler-Weaver's license plate.

Joann Brown'southward check-in call to Amina Nobles helped police connect Wheeler-Weaver to the spot where she was kidnapped and the abandoned house where her body was found.

Bassania Daley and LaMia Dark-brown discovered the discarded scarlet extension, which made Sarah Butler'south disappearance look even more suspicious. Sleuthing past Daley and her friends also established Wheeler-Weaver'southward methodology: using his phone to rail women, offering cash, and then rushing them to meet.

Past finding Wheeler-Weaver online, and luring him into a trap with police, the women risked their lives.

He believed he was hunting his next victim. In reality, the women were hunting him.

Even after Wheeler-Weaver's abort, the women did non cease.

Three weeks subsequently she narrowly escaped, Taylor read a newspaper story that Wheeler-Weaver had been arrested in connection with Sarah Butler'due south murder. He was arraigned in Newark on December. 13, 2016.

Taylor isn't fond of courthouses. And she hates cops.

She high-strung downwardly her fear. She went to the courthouse anyhow.

"I was nervous," she recalled. "Every fourth dimension I phone call police, I always end up wishing I didn't call."

As Wheeler-Weaver was arraigned, Taylor sat in the courtroom. After the brief hearing, she approached Wells, the lead prosecutor.

Taylor was the merely person who could necktie together all the threads of Wheeler-Weaver'due south murder spree: his phone, his digital stalking, rape, strangulation, and wrapping his victims' heads in tape.

"She was very important," Wells said. "We like to think nosotros could take prosecuted this instance successfully without hearing from Ms. Taylor. Merely there's no question that her testimony made information technology easier."

Taylor testified for an entire day. She described in open court the failures of Elizabeth law.

"If the police had believed me, Sarah Butler would withal be alive," Taylor said.

Taylor sat in the witness box and faced Wheeler-Weaver. She told jurors how she robbed this human. Lied to him. How he strangled her, and how, moments later, she played him for a fool.

"I wanted him to see me," Taylor said. "I wanted him to know that information technology was me."

Reporters:Christopher Maag, Julia Martin, Tom Nobile, Keldy Ortiz and Svetlana Shkolnikova. The story was written past Maag.

Photography:Chris Pedota, Anne-Marie Caruso, Mitsu Yasukawa

Video documentary: Chris Pedota and Chris Maag

Editing:Ed Forbes, Alex Nussbaum, Candace Mitchell

Copy editing: Susan Lupow

Drone footage: Tariq Zehawi and Danielle Parhizkaran

Visuals editing: Sean Oates, Nancy Pascarella, Michael Five. Pettigano, Paul Wood Jr.

Social media: Elyse Toribio

Graphics and illustrations:Kayla Golliher, Javier Zarracina

Digital production and evolution: Kayla Golliher, Andrea Brunty, Michael Babin, Kyle Omphroy, Craig Johnson

This story is based on evidence presented by 45 witnesses at Wheeler-Weaver'south trial, which lasted nine weeks in belatedly 2019. It also is based on more two dozen interviews with investigators, prosecutors, friends, family unit members and neighbors of the killer and the victims, and lengthy interviews with the killer'south solitary survivor. NorthJersey.com and the U.s.a. TODAY NETWORK New Jersey too reviewed dozens of police records and police surveillance footage to produce this account.

Source: https://www.northjersey.com/in-depth/news/crime/2020/02/03/how-group-women-stopped-nj-serial-killer/2661900001/

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Robert Weaver Stop Me Before I Kill Again"

Posting Komentar